Organizing Early Modern Texts

This essay is a slightly revised version of a presentation from the 2012 Renaissance Society of America meeting in Washington, DC.

The rapidly growing archive of early modern texts online presents significant new opportunities and necessities for the ways in which we organize it. Addressing such challenges raises important questions for both skeptics and boosters: Are new methods of organization resulting in virtual but less reliable finding aids? Do pressures of modernization encourage resource-strapped organizers of early modern texts to adopt whatever technologies are easiest? Are we really taking advantage of new archival possibilities?

Anecdotal Prelude

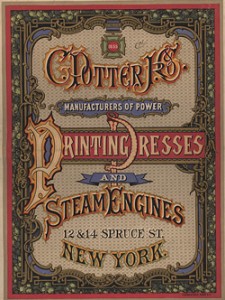

Improper use of technology—or perhaps misplaced technological priorities—is a danger that we might already be falling prey to. We might be able to better frame the digital challenges facing early modern texts and modern organizational technologies with an analogy to the world of printing in the later 19th century. It was then that letterpress printers found themselves competing with newer and sexier printing techniques, like chromolithography and engraving. Those products were hand-drawn and therefore allowed much greater freedom in design. Soon after, technical advances in letterpress print technology itself (brighter and faster drying inks, new typesetting techniques) allowed letterpress printers to flex their own design chops, and to develop what came to be known as “artistic printing.”

Despite the name, it wasn’t really artistic at all—at least not in the sense that it could be characterized by superior aesthetics per fine art standards. The predominant feature was ornamentation—excessive ornamentation: grandiose borders, highly stylized typefaces, bizarre color schemes, and non-linear design elements—employed to rival materials printed with newer printing technologies, even when those weren’t characterized by such ornamentation. Printers’ content was thus dictated by technology; the medium had overtaken the message.

Critics reacted strongly against printers making their content subservient to “barbaric” excessive ornamentation and “degenerate” ostentatious flourishes. They lamented how printers focused on the immediate and low-hanging technological fruit ahead of fundamental typographic principles. The extra ornament was considered a sham, a form of concealment.

Where letterpress printers did not, we must constantly reflect on our priorities and values as we embrace new technologies for organizing our overwhelmingly large and still growing archive of early modern sources. 21st-century organization of early modern texts must not be seen only as a technological prosthetic that enhances traditional practices, but rather an opportunity for creating and engaging with a new kind of archive.

Modern Information Overload

As we all know, information overload is not new. One salient reminder comes from Ann Blair and her book Too Much To Know, in which she describes how early modern scholars developed various procedural strategies and textual apparati (many of which we still use) to help find and to organize the vast amount of information flooding into their personal libraries. In part, we have the same problem; we too have access to more texts than ever before.

Having access to more texts facilitates more opportunities for applying our traditional methods for organization. We might be tempted to emulate our early modern predecessors, but with modern equivalents—no longer curating shoeboxes of 3×5 cards, but rather Zotero libraries; perhaps moderating virtual group libraries instead of emailing bibliographies. On the whole, we as did early modern scholars tend to think in terms of individual technology solutions with some social tentacles, like Zotero and RefWorks. Even on the web, we do this also. We continue to create isolated databases, search engines for them, and even lists of links to help organize and connect early modern texts. But are we creating these because they are the most productive, or because they are most easily accessible technology “solutions?” Have our databases become our ornamental borders?

Unlike previous instances of information overload, however, organization is no longer an individual problem. Rather, it’s one that exists at the level of scholarly societies and broad research communities (notice that i’m not including libraries; more on why later). Our unprecedented access to the early modern period means that we have the potential for a vastly larger and much richer archive than we’ve had before. We must take an active role in organizing that archive to make it available, visible, and fully usable.

I want highlight two facets of the digital archive that will be crucial as digital methodologies become more integrated with our research practices: metadata and text transcriptions. In other words: creating and connecting texts.

2 important caveats

1) I want to emphasize at the outset that both of these are fundamentally social challenges, not technological ones. This is not about what technical standard to follow. This is not about which interface components or which ornamental border to use. These are important questions, but ones that should and will naturally follow a deliberate attempt to make archival content a value problem rather than a technology problem.

2) When speaking about metadata and text–and maybe even the digital humanities at large–skeptics often immediately seize upon the very impersonal and non-humanist kind of inquiry that seems to underlie techniques like text mining, or any vaguely quantitative methodology. Aren’t we simply outsourcing our interpretive powers to complex algorithms and code? NO. These are tools to help us do our work, not strategies for having the computer do interpretive work for us. The goal is to make the fullest use of the early modern record that has come down to us.

Ethics and Metaphysics of Metadata

It’s hardly news that finding relevant online resources can be problematic for many early modern scholars. As we all know, the bibliographic data we rely on—whether from Google Books, HathiTrust, Internet Archive, and even fully controlled catalogs like the Library of Congress—can be a mess, confused by lengthy and sometimes bizarre titles, language variants, non-standardized author names, foreign characters, uncertain dates…the list could go on and on.

Rejoinders against such mess typically frame these problems as repository problems (eg Google Books has failed us because its metadata is so poor). The problem here is that this kind of thinking embraces the traditional delineation of the researcher as a mere consumer of data. But using poor metadata as the sand in which to bury one’s head in is not a productive way forward. We need to consider the ethics and metaphysics of metadata: Exactly what does it take to create metadata? Whose responsibility is it?

It seems that many metadata critiques treat metadata as objective, descriptive information that simply should be correct. But anyone who’s ever produced any serious amount of metadata knows that it’s quite subjective, confusing, and takes considerable expertise to do properly—especially for early modern sources. Because we’re the ones with this expertise, we must be not only consumers, but also producers of this data.

But isn’t creating and improving metadata the work of librarians and archivists, you ask? Surely, research scholars don’t have the time, inclination or expertise to deal with metadata. We produce knowledge, not metadata!

Except that we don’t live in the binary producer/consumer world anymore. Even if we did, there is simply too much data to deal with. Its stewards simply do not have all necessary expertise or resources to organize it most effectively and flexibly. Without doubt, this involves plenty of technical challenges (standards, interfaces, infrastructure). But these are trivial in comparison to the real challenge: shifting community expectations that erroneous metadata can and should be edited by researchers themselves. And while we’re at it, we might broaden our view of metadata to include not only the usual fields (author, date, etc), but additional description as well (abstracts, section headings, keywords, etc) that makes the texts more findable.

The idea that we share a communal responsibility for metadata requires changes to typical research practices that need to happen more or less simultaneously.

a) The research community must recognize the scholarly value of this work. Making such contributions is the kind of peripheral scholarly work that we already do because we recognize its importance and necessity, such as peer review, review articles, editing, chairing sessions, etc. And we have to recognize that such effort does not have to stem from sheer altruism, as it helps us take fuller advantage of the vast archive we have at our fingertips. It’s far from value neutral, and it requires considerable expertise.

b) Repositories of information need to facilitate metadata suggestions from the scholarly community. This does not mean that they ought to adopt, anonymous, real-time data revisions. Instead: a controlled, but open community effort to improve data. As researchers, we must voice our desire to help make data more usable. Librarians and archivists are nothing if not sensitive to the needs of their constituents.

Framed in this way, the problem isn’t the erroneous metadata itself (woeful as it can be). The problem is that a) we continue to reinforce a division of labor that doesn’t make sense anymore, and b) remain bit too myopic about the kind of work we value as a scholarly community.

Early Modern übertext (creating and using text)

Textual organizational challenges are not just about the connective tissue between texts (like metadata), but also part of the challenge of helping to produce the texts themselves.

There is no doubt that the rhetoric of the digital humanities embraces the bird’s eye view of text. Digital methodologies leverage the computer’s ability for mindless drudgery to help us do and see more than we would otherwise—and hopefully make discoveries that would otherwise go unnoticed. Like repairing metadata, such a perspective suggests a new expectation for our archival work: making text/data visible and available. Again, this is not so we can get the computer to interpret it for us. It’s about futzing around with our hermeneutical prism and engaging with the historical record by all available means (and texts).

Ongoing digitization projects, both small- and large-scale operations, are making the early modern world more accessible each day. Resources like Google Books, HathiTrust, EEBO, ECCO, etc, make access to primary sources easier than ever—at least in terms of facilitating our traditional strategy: search, find, and read closely. But image-only archives stored in carefully constructed databases, as useful as they are for improving accessibility, cannot be our only interest. We must not let them become our ornamental borders.

To truly understand the early modern text (writ large), we need textual transcriptions. Now I am not suggesting that we all spend our time creating transcriptions for our unadulterated love of plain text. But we do an awful lot of work in transcribing for our own scholarship. Imagine all the personal notes stashed on hard drives, all the long quotations stashed in notes in nearly impossible to find monographs. What would our historical archive be like if we had access to that text? What if we put them all together? How would our interpretations be different? What else could we find out?

This isn’t as far-fetched as it may seem. The many (wildly) successful transcription projects (Transcribe Bentham, etc.) suggest the success of collaborative participation, patience, and persistence. The problem is that we don’t value this work as much as we should. As with metadata, it should be considered important scholarly work (but perhaps not scholarship per se). Various technologies and standards with linked open data are creating the connective tissue. But we need the bits to connect.

Several problems with text creation that require attention (merely mentioned here):

- Favoritism: Text creation projects tend to favor the texts we already know—a bias of funded projects that must justify expense with appeals to established utility to a broad audience.

- Access: Full-text resources tend to be behind expensive pay walls, and usually mediated by well meaning but clunky search engines.

- Visibility: Our typical practices don’t support publishing these texts. We need to supplement our traditional forms of scholarship with co-publications on our blogs.

- Authority/Expertise: How do we know where metadata and text have come from? Do we trust them? We learn to make these judgments about scholarship generally; we can learn to do it for data, too.

The reason I mention these challenges (even so curtly), is to point out that they are neither library nor archive problems, nor are they reasons to avoid creating texts. They are our problems that will continue as long as we maintain a too narrow definition of useful work that doesn’t include creating and connecting texts, and as long as we expect other people to make texts available and useful for us. Open access is not a challenge for only archivists, librarians and publishers. It’s one that pervades the entire scholarly community to publish and preserve work they consider valuable.

More importantly, these problems persist especially when we employ individual organization solutions, even ones that attempt to aggregate information. We don’t need more search engines or more APIs. We need visible text. Use a database to store your text, but don’t make me interact with it. Databases are like closed stacks; the best retrieval mechanism doesn’t make either of them particularly visible and usable. Even if we have our eyes on the prize of linked open data, we must not forget about this first crucial step of creating texts to link to–and they should be openly published online.

So why bother creating and organizing such a textual archive? Not everyone will be interested, and that’s fine. But one can hardly ignore the potential here in terms of getting out of scholarly ruts. The literary critic Barbara Herrnstein Smith has suggested that the literary text acts “to shape and create the culture in which its value is produced and transmitted and, for that very reason, to perpetuate the conditions of its own flourishing” (Contingencies of Value, 1988). We could say the same thing about our digital organizational practices as well, as many important techniques that take broad views of texts and data can only be realized when we have an adequate, accessible and visible archive of digital, discrete, malleable, text. If we privilege only traditional archival strategies, we miss out on virtually all historical perspectives that aren’t exposed by those methodologies.

One obvious case is massive searching, which is self-explanatory. More important is malleability: combining unusual sets of texts to get a bird’s eye comparative view. This should not instantly conjure images of massive scatterplots and necessarily large-scale efforts. Small-scale work is also extremely valuable, especially when combining text across archives and disciplinary boundaries.

One of the most important reasons to value the creation of full text is the way searching is moving from linear to algorithmic searching. Our organizational strategies (databases, lists, catalogs, etc.) tend to re-enforce traditional, linear research practices. But the future of searching is not simply finding what you’re looking for. Having more text (and better metadata) allows us to take advantage of finding not only what we are looking for, but also what we’re not looking for—but should be. Imagine a “show me more like this…” feature that worked for our primary sources. Algorithmic searching is, of course, what Google does, but I’m not suggesting that their mysterious PageRank algorithm should reign over our sources. But as we think about how to organize an unprecedented volume of text, we also have to think about future access technologies. We need to think about the principles of data architecture (typography), and to be sure they are not being applied as technological band-aids (fanciful mauve borders).

Again, all of these efforts (fixing metadata, text encoding, creating and publishing transcriptions) require an expansion in the kind of scholarly work we value and reshaping relationship between producers and consumers of data. Simply waiting around for better data or better tools will make for both inferior tools and scholarship. While there are many examples of text creation projects—and such projects have produced excellent results—they tend to be specially grant-funded projects that create unnecessary labor bottlenecks. This model is wholly unsustainable. Worse yet, the products of such projects tend to reside in databases that we say are open, available, and connected, but are only trivially so, since so few people know about them or can access them.

Imagining the Future

If what I’ve described sounds like some fantasy utopia…let me reassure you: it is. But the imaginative possibilities are indeed tantalizing, and even such a utopian vision should guide our values and priorities. Necessity might be the mother of invention, but imagination is its milk.

With such a vastly accessible archive at our fingertips, Mike Witmore (who commented on the conference panel where an early version of this essay was presented) asked if we will lose our ability to ask good questions? Or will we simply be tinkering with texts because they are there? Will our questions still be meaningful? I interpret this as: Will our scholarship be reduced to overwrought font faces and massive visualizations that merely add knowledge without value? It remains to be seen, but I don’t think that fully exposing and connecting our early modern texts (and ways of accessing them) will jeopardize our critical faculties or ability to identify and frame interesting questions. Various digital humanities projects have already started to do that. As do new visualizations, a new kind of archive will facilitate new kinds of questions–ones that cannot possibly grow out of the textual archive the way we have traditionally organized it.

In terms of establishing values, our teaching is crucial. As educators of future early modernists, we have to increase awareness of and discuss new textual analytical techniques, and how to establish their requisite infrastructure (like metadata and the value of textual openness) in our courses. Furthermore, our teaching can contribute to the project of making more texts available and visible. We can take advantage of the necessary repetition that happens in both grad and undergrad training to shape the early modern archive into its most usable form. Ars longa, vita brevis. Other sessions have already suggested what a great process transcription is for teaching about editing and understanding the notion of a text.

As with our earlier letterpress printers, we’ll have our share of overly ornamented communication failures, where technological fascination obscures analytical objectives. And that’s okay. In a way that typical scholarship does not, we must embrace productive failure—tools, interfaces, processes that help us shape the resources at our disposal. Best practices for improving metadata or associating text with images are unclear: it’s not at all obvious whether we should be using Betamax or VHS right now. In the end, it doesn’t matter, as long as we must value the larger goals more than any particular technology.

We have to be thinking of books and texts not only in their contemporary contexts, but also in their modern digital contexts as well, and how we employ technologies to connect them to as many other relevant texts as possible (obvious: author, year, place, subject; cooler: word frequency, tone, style), and how we can profitably put these texts in conversation with each other. That is the organizational challenge ahead. At a superficial level, it’s not at all a new problem. Beneath the surface, though, it’s an entirely different kind of challenge that has the potential for an entirely new kind of early modern text and interpretations of it.