Learning to Read. Again.

What does reverse outlining have to do with text mining? He might not realize it, but Aaron Hamburger, in a nice Opinionator essay that enumerates the virtues of outlining in reverse for creative writing, has made a fantastic justification for new research techniques of the digital humanities. Using his piece as a springboard, I argue here that historians would be well served to expand their notion of what it means to read–as oppose to analyze–a text or set of texts with digital methods.

When you don’t have a second pair of eyes nearby that can give you a sense of what you’ve done, sometimes it helps to trick yourself into seeing your work in a new light, by printing it out, changing your font, reading your work out loud.

This quote from Aaron obviously addresses the trouble we have getting out of our own heads, even when we’re reading words on a page. The technique of reverse outlining provides a new perspective, in which you might end up “doing a little math” to recognize that you’ve written too much or too little about something—even when you thought (=assumed) you had done otherwise.

At least at first glance, a technique like reverse outlining applies more to revision than to research itself. After all, historians have become very comfortable at making sense of their sources when that means deciphering words in sentences: we like to think about who wrote them, their motivations, and the extent to which we can take that person and those words at face value. We think we’re good at it, and we have a certain cluster of letters after our name to prove it.

But the process of reading is hardly less biased when we’re reading historical sources than when we’re reading our own work. This is true because we are, in no small way, making those historical sources into our own work. It’s also true because just as reading something we’ve written inadvertently triggers neurons to make us read or think something that isn’t evident in the text itself, reading historical sources makes invokes the same kind of ancillary conceptual framing that lends an inherent bias to our reading, no matter how strong our drive toward objectivity.

It’s hardly necessary at this point to dredge up the debate about historical objectivity. But if we’re serious about reading as objectively as possible, then why not embrace multiple ways of reading? To embrace digital history is to expand what it means to read a text.

Just to be clear, I do not mean that we should necessarily embrace a kind of distant reading that assumes one has lots of historical data/texts that must be analyzed. Despite all the rhetoric about distant reading and big data, they are often totally irrelevant to what most historians do. But other ways of reading sources are useful regardless of how many sources there are. Allow me to provide a trivial but informative example.

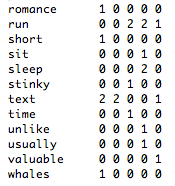

When I first contemplated the goal of creating a document matrix (and how it could be considered a corpus) my reaction registered somewhere marginally above abject disdain. This matrix is not a corpus; it is a grid of numbers. Obviously, this was just another example of some computer scientists over-simplifying complex humanistic data to numbers again.

Everyone obviously knows that a matrix and a set of texts are different things! Why pretend otherwise?!

Of course this knee-jerk response is exactly why so many historians remain skeptical of embracing new methodologies, even as they would whole-heartedly agree that a reverse outline—just another representation of a text—is a good way of forcing a new and productive reading of an old (or too familiar) text.

It was only in creating a document matrix myself when I started to understand more of the steps behind it and to see the numbers as a perfectly nice representation of the text itself. To be clear, I did not have a Matrix-like Neo moment when I could move seamlessly between columns of green characters scrolling up my terminal console and the words in the individual documents themselves. That would actually defeat the point, anyway. (I can, however, stop bullets in mid air.)

I began to see the document matrix as a perfectly valid representation of the text itself—a version that could be read in a different way from the other representation I had (the documents themselves). This wasn’t really distant reading; I was only using, like, 4 texts of a few sentences each for the purposes of completing the tutorial.

I imagine that a typical historian's response to the idea of reading a document matrix or other visualization is to reject the presumption that a grid of numbers should be considered a text or a set of texts at all. We tend to assume we know a text when we see it (even considering its many possible forms), and a document matrix simply isn't one. But it's the interpretation that matters and there is plenty of room to interpret a matrix or any other representation—just as much as reading words in sentences.

I suspect one reason that such a numerical approach to texts incites fear and loathing in most humanists is because of a totally erroneous assumption of reliability, a fallacy predicated on the notion that calculations or statistics are inherently less ambiguous than the hermeneutics of language. Such a position also usually assumes that something like a document matrix should be considered as a de facto “analysis” of the texts—yet one that we can’t really trust because computers are notoriously bad with extracting meaning from human language.

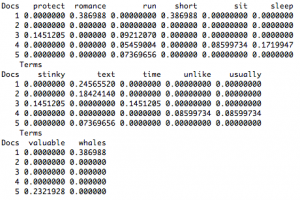

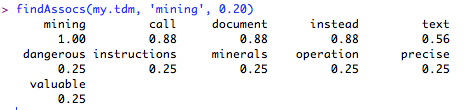

We must distinguish between representing texts and extracting meaning. Although it can be said that a scatterplot of word frequencies offers a numerical analysis of sorts, it does not pretend to offer a humanistic one. Rather, it less ambitiously provides another representation of the text itself. A chart of word frequencies or a list of topic models is no more or less authoritative a reading than using the words themselves. Of course what's interesting about the words is the ideas they represent. But the same goes for _any_ representation, including how one can get new ideas about what a text “means” by inspecting the statistical relationships between words and documents. Obviously it's no substitute for “real” reading, but that's precisely my point, and the whole motivation for something like reverse outlining.

One could argue that any such transformation has corrupted the original text so much that the original and essential meaning has been irretrievably lost. But haven’t we yet unyoked ourselves from the imperative to discover the essential meaning in any text? Do we not all read things differently anyway? Don’t multiple readings aid in analysis?

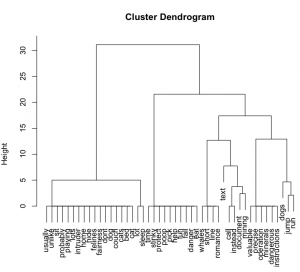

As everyone should know by now, looking at visualizations of texts is a form of exploring and should be taken not as analysis, but exploration. One might respond, then, by saying that a document matrix on dendrogram that shows word relationships cannot be read, although perhaps it can be explored. The traditional historian might then reply that exploring is fine, but eventually one has to read, because that is how we make true sense of things. Also fine.

But this view is okay only as long as we recognize that there are lots of ways of reading that don’t involve looking at words in some predetermined order. We must train historians not only to embrace exploration, but also to embrace multi-modal ways of reading—ones that are not necessarily exploratory, or at least no more so than the traditional act of reading itself. Art historians, for example, often read images, not just explore them. Those images don’t tell the whole story, nor do a set of topic models, nor does a text.

It may be tempting to call such a digital reading a distant or perhaps abstracted reading—one that isn’t connected to the text and therefore less useful. However, something like a document matrix is arguably more connected to the original text because its bias and presumptions stem directly the algorithms and whatever dials and knobs the reader has fiddled with during the course of “reading” with a tool like R—if only our own biases in reading could be known or changed so easily! Of course these biases lead to misreadings, but only in the same way that our regular ways of reading do. Let’s just be honest: all ways of reading are flawed. It’s silly to discard a technique because it doesn’t automatically reveal the same relationships that we expect when reading traditionally.

Most of the debates of the merits of distant reading have focused on the distance rather than the reading. The common language used to describe the step of understanding statistical representations like a document matrix is to “interpret the results.” There may be unfortunate consequences to approaching the problem in this way, namely in how it foregrounds a “result” of an analysis rather than creating a representation of a text that needs to be interpreted like the version of texts with words in it. There are no results to interpret any more than a paragraph of text is some kind of result. It is merely one possible expression of an idea.

And more ways of reading increase our interpretive powers. To claim that mathematical expressions of texts have nothing to offer in the way of interpretation is to say that abstract and unexpected representations cannot provide useful readings. Which is also to deny the fundamental premise of visualization and to embrace the fallacy of infallible readings. Please don’t.

Of course the elephant in the room wears a giant neon sign that reads: “So what?!” If these techniques are so great, why hasn’t anyone rewritten historical interpretations based on such techniques?

But we’re still learning to read in this way. And my point is that new ways of reading are a good thing, even if such “text mining” techniques don’t immediately reveal the gold nuggets that everyone’s missed up until now. Multiple readings help us be better historians, regardless of whether one way of reading can be seen as (or actually is) “better” than another.

Looking at texts through tools like R is indeed a kind of reading in itself. Far from the presumption of objectivity, they embrace the hermeneutical fuzziness inherent even in a statistically-derived document matrix. As with traditional reading, there is considerable reading and interpreting to do be done even on numerical representations of texts. Perhaps thinking of it this way—as reading—can make it seem not like digital work, but simply historical work.

We can (and must) learn new ways of reading texts, and to embrace mathematical abstraction and visualization as interpretative allies rather than block-box enemies. The typical humanist creation of meaning from text is no less black-boxy that reading the text through mathematical lenses. These new ways of reading are not the savior of the humanities, and they do not guarantee new insights into anything. They may be utterly useless for your purposes, in the same way that trying to analyze sources through a Marxist or a Feminist lens may be totally unhelpful. But we expect good historians to carry a large bag full of lenses, and tools like R are just another one to bring various textual features into focus.